Who I Am

GREGORY BURGESS

Candidate for U.S. Congress California's 2nd Congressional District

About Gregory

Gregory Warren Burgess isn't your typical congressional candidate. He's a special education teacher, a public health officer, a clinical engineer, and a working-class American who has held more jobs than most politicians have held photo ops. From delivering mail as a USPS carrier to training AI-assisted medical devices to help hospital professionals determine blood loss in patients undergoing Labor and Delivery or General Surgery, Gregory has lived the life that most of our representatives only talk about.

For ten years, Gregory worked as a special education teacher, developing individualized learning plans for students with autism, ADHD, learning disabilities, and behavioral challenges. He knows what it means to meet people where they are, to adapt to their needs, and to never give up on someone because they learn differently. That same philosophy drives his approach to public service: listen first, understand the problem, and find solutions that work for real people.

Gregory holds a Master's degree in Public Health and served as a Quarantine Public Health Officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during some of the most challenging public health crises of our time. He conducted disease surveillance, contact tracing, and community education, working on the front lines to protect public health when it mattered most. He has seen firsthand how federal bureaucracy can both help and hinder local communities, and he believes our healthcare system must work for patients, not insurance companies.

Most recently, Gregory worked as a clinical engineer training healthcare professionals on AI-assisted surgical blood-loss monitoring technology at a medical device company in Los Altos. Before that, he worked in logistics and shipping, managed operations in Los Altos, CA, at group homes, and delivered mail for the United States Postal Service. He understands technology, logistics, healthcare, and the dignity of honest work. He's not afraid to get his hands dirty, and he knows that every job matters.

Why I’m Running

Gregory is running for Congress because he's tired of watching Washington D.C. make decisions for California communities that have nothing to do with the realities on the ground.

He's running as a No Preferred Party candidate, a new political movement focused on practical solutions, local control, and fiscal responsibility. Greg believes that the best government is the government closest to the people, and that communities should control their own destinies—not unelected bureaucrats in distant capitals.

What I Stand For

A "Pay-For" Promise: Fiscal Sanity Gregory believes we cannot borrow our way to prosperity. Every proposal in his platform adheres to a strict "Pay-For" model. We will fund our priorities by closing corporate tax loopholes—like the deduction for excessive executive compensation and the "carried interest" loophole for hedge fund managers—and by rescinding unspent, unobligated federal grant money. We won't add a dime to the deficit or to your taxes.

Defending Our Homes from Wildfire We are done with reactive spending that only shows up after the smoke clears. Gregory is proposing the National Wildland Fire Response and Forest Solvency Act, which establishes a specialized "Federal Fire Brigade"—a civilian force dedicated to year-round prevention and forest hardening. Funded by a market-based Carbon Resilience mechanism, this bill shifts the focus from suppression to survival, protecting our communities before the fire starts.

Healthcare Where You Live Rural residents shouldn't have to drive four hours to see a doctor. Gregory’s Rural Health & Tele-Specialist Access Act cuts through red tape to allow local clinics to connect patients with top-tier specialists across state lines via high-speed telehealth. Furthermore, his Family and Solo Elder Home Care Preservation Act ensures that our seniors can afford to age with dignity in their own homes, supporting the caregivers who make that possible.

Respecting Those Who Serve Essential workers deserve more than applause; they deserve financial respect. The FRTLE Act (Financial Respect for Teachers, First Responders, and Essential Public Health Workers) will eliminate federal income tax on the first $50,000 of wages for the teachers, cops, firefighters, and nurses who serve our communities. This is an immediate, effective pay raise for the backbone of our society.

Housing for the People Who Work Here Our agricultural and tourism economies are collapsing because workers cannot afford to live here. Gregory wrote the Wine Country Workforce Housing Partnership Act and the Affordable Housing & Community Protection Act, which incentivize local zoning reforms and provide tax credits to build housing specifically for the "missing middle"—the teachers, farmworkers, and service staff who are priced out of the market.

Investing in Families and Skills We need to make it easier to raise a family and build a career. The Working Parents & Secure Childcare Incentive Act provides tax credits to businesses that build childcare facilities on-site or nearby, letting parents stay close to their kids. For our youth, the Civilian GI Bill & Trade Skills Independence Act offers a debt-free path to trade school for young Americans willing to serve in high-demand fields like forestry and construction.

My Commitment

"Your vote matters more than your money to me," Gregory often says. He's not taking corporate PAC money. He's not beholden to party bosses. He's running to give power back to the people who actually live, work, and raise families along California's Coast and Northern Counties.

Gregory believes in transparency, fiscal responsibility, and sunset provisions for every program. He thinks that if a government program can't prove it works after ten years, it should expire. He thinks politicians should be accountable to the people they serve, not to the special interests that fund their campaigns.

Personal Life

Gregory’s diverse work experience—from teaching special education to training Artificial Intelligence to delivering mail—gives him a unique perspective on the challenges facing working families in the Coast and Northern Regions of California’s District CA-2.

He believes that public service should be just that: service. Not a career. Not a path to wealth. But a temporary duty to stand up for your neighbors and fight for what's right.

The Choice

In 2026, voters in California's 2nd Congressional District will have a choice: more of the same partisan gridlock, or a new voice that puts local communities first. A teacher who understands that every student learns differently. A public health officer who knows that one-size-fits-all mandates don't work. A working-class American who has held the jobs that real people hold.

Gregory Burgess is running for Congress to give power back to you.

"You and your vote are more important than your money to me." — Gregory Burgess

Some people leave behind a career. Some leave behind a family.

And some leave behind something rarer, an ethic.

Politics is often about the promises we make for the future, but character is defined by where we come from. My values, independence, foresight, and a refusal to waste, were not learned in a classroom, but in the garden of a woman who saw the future long before it arrived.

Before Recycling Had a Symbol

I consider myself an environmentalist because I was raised by one.

My mother, Wanda Lee (Swett Burgess) Ballentine, informed others under the email monikers RagingGrannie and EcoNag, and helped stop ozone layer depletion and protested a Hyundai semiconductor plant in Oregon. She raised us recycling and composting before it became a thing with three circular arrows. We had a can for various metals, a can for glass, a can for aluminum, a can for paper, a can for compost, and a can for the dump.

She worked a vegetable garden (I hate weeding to this day, but I always enjoyed the fresh peas from the pod and the strawberries and wild blackberries growing at our back fence). We had chickens, until the local dogs killed them, and rabbits, all in suburban Mill Valley. She did this because she grew up during WWII and believed that "moving on" from the Victory Garden and recycling campaigns wasn't progress, it was amnesia.

She was right.

A San Francisco Native

Wanda Lee Swett was born in San Francisco and raised in Belmont on the Peninsula. She came of age during a time when California was transforming from agricultural paradise to suburban sprawl, and something in her resisted that transformation from the very beginning.

At UCLA in the late 1950s, she was a member of the Human Relations Council, a student organization dedicated to promoting understanding across racial and religious divides. This early work planted the seeds of her lifelong conviction: that individual problems, whether social or environmental, have systemic roots and require collective solutions.

She earned her Master's in Social Work and married Dr. Earl Burgess, a psychiatrist. Together they raised their family in Mill Valley, Marin County, from 1966 to 1985, my sisters Amelia and Cynthia and me. But while my father treated patients in his office, my mother was developing a different kind of cure for what ailed American society.

A Philosopher of Family and Land

In 1972, my mother's ideas reached a national audience when her chapter, "Learning to Cooperate: A Middle-Class Experiment," was published in The Future of the Family, alongside contributions from Dr. Benjamin Spock, Gail Sheehy, and other leading thinkers of the day. In it, she argued that the isolated suburban household, where every family owns its own lawnmower, its own washing machine, its own car, was both psychologically destructive and ecologically wasteful.

Her solution was not a government program but a revolution in daily living: cooperation. Share resources with neighbors. Pool childcare. Grow food together. Build community through the practical acts of everyday life.

During the devastating California drought of 1977, ABC7 News featured my mother demonstrating water conservation techniques, using a pump to recycle laundry water for her garden. She wasn't just theorizing about sustainability; she was living it, sometimes pushing the edges of what was permitted by building codes.

The Activist Years

My parents divorced in 1981. In 1990, when we all had grown,my mother moved to Eugene, Oregon, where she lived with her mother and threw herself into environmental activism with renewed intensity. Family, to her, was never disposable. Care was something you did, not something you claimed.

She wrote for local publications about the dangers of corporate power over environmental policy. In 1996, she was among those who opposed Hyundai's massive semiconductor plant near the Willamette River, a facility that would discharge millions of gallons of wastewater daily and use over 700,000 pounds of hydrofluoric acid annually. She understood, decades before most Americans, that "high-tech" industry could be just as environmentally devastating as smokestacks and strip mines.

As early as 1992, she was active on the internet, then still the province of academics and early adopters, spreading information about protecting the ozone layer. She shared detailed guides on avoiding chlorofluorocarbons and pressuring industry to find alternatives. The Montreal Protocol would eventually prove successful, and activists like my mother were part of that victory.

A Leader in the Climate Movement

In July 2003, while living in Cleveland, Ohio, my mother helped organize the Global Warming Crisis Council. This was before Al Gore's documentary, before climate change was front-page news. The Council connected over 6,000 activists worldwide, and my mother served as a primary contact point, the person you emailed if you wanted to join the fight.

The Council's principles reflected everything she had learned over four decades of activism. They called for an 80% reduction in fossil fuel emissions. They urged people to "reject the jet" and take vacations without air travel. Most memorably, they asked Americans to "depave your driveway", to literally tear up the asphalt and reclaim the soil for growing food.

That phrase captures my mother's philosophy perfectly: the driveway is a symbol of isolated, car-dependent, fossil-fuel-consuming suburban life. To depave it is to restore both the earth and the community.

Never Stopping

From 2003 to 2017, living in Eagan, Minnesota, my mother continued her activism. She submitted public comments opposing sulfide mining in the Boundary Waters watershed. She signed petitions to protect the Gray Wolf. She engaged with every regulatory process that affected the environment she loved.

Now 87 years old and living in Petaluma, California, back in the landscape of her youth, she represents what it means to be a citizen in the deepest sense: someone who never stopped believing that individual choices matter, and that the future is something we owe to one another.

Her Legacy

Wanda Ballentine's legacy is not a single accomplishment, a single job title, or a single public victory. It is something far more enduring: a family raised with conscience, a worldview rooted in responsibility, and a lifetime of refusing to look away.

She taught her children that the planet is not a metaphor, it is a home. She taught that "environmentalism" is not a political identity but an obligation. And she taught that real values don't require applause.

Why This Matters

I am running for Congress because I believe in showing my work, in being transparent about what I stand for and how I'll achieve it. That belief comes directly from my mother. She didn't just talk about environmental values; she lived them, in our backyard garden and our recycling cans and our compost bins, long before anyone thought it was fashionable.

She understood that the environmental crisis and the crisis of American community are the same crisis. We overconsume because we're isolated. We waste because we don't share. We destroy the planet because we've forgotten how to be neighbors.

The Victory Gardens and recycling campaigns of World War II proved that Americans could live differently when we understood it mattered. My mother never accepted that we should go back to wasteful isolation just because the war was over. She kept the garden growing. She kept the bins sorted. She kept fighting.

She was right. She still is.

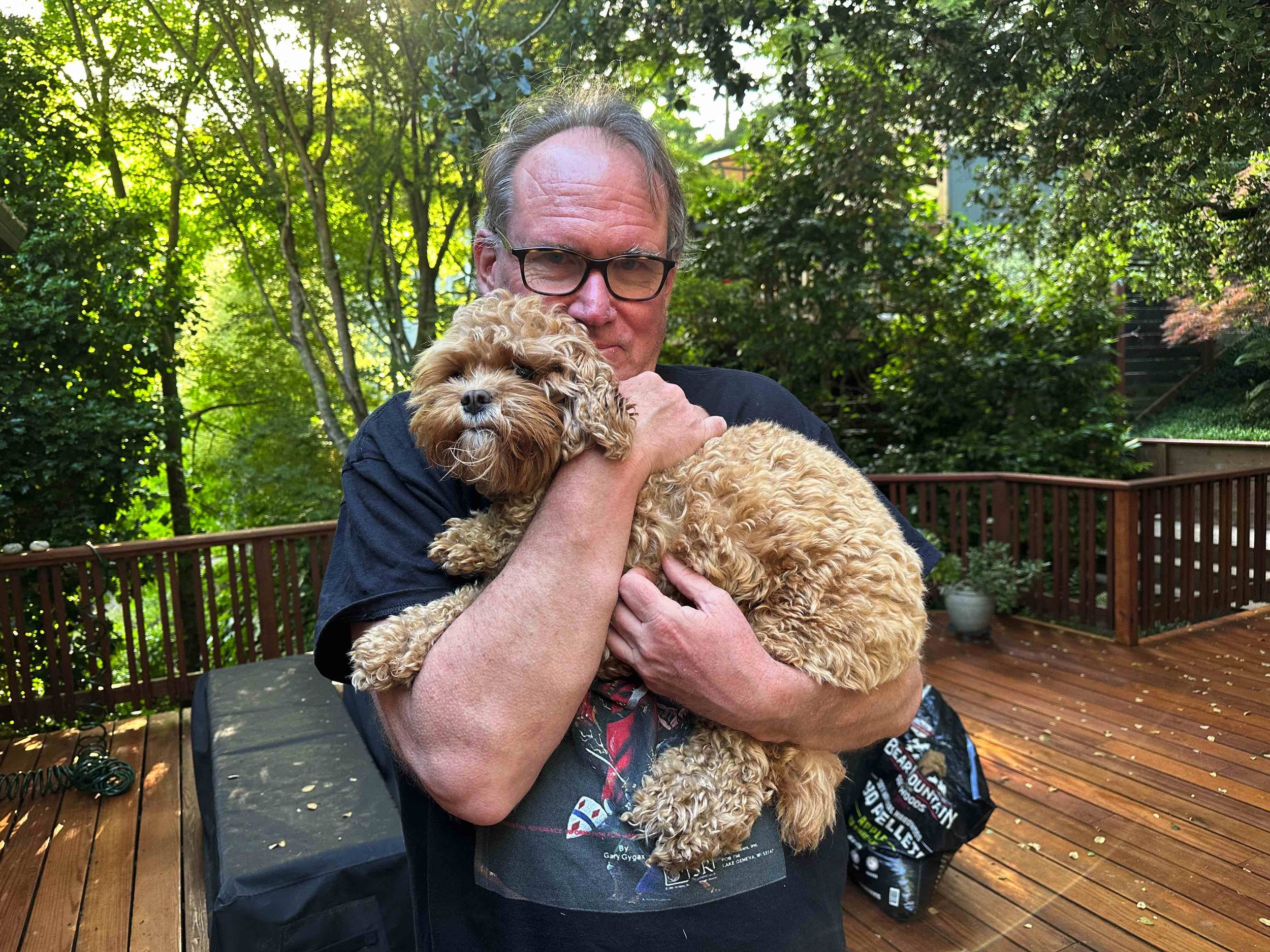

My Mom

Contact us

Interested in working together? Fill out some info and we will be in touch shortly. We can’t wait to hear from you!